Big if True

predictions for the future of transportation

The students have left Champaign, so I can get back to my real jobs: gardening and posting. These go together: while gardening, I’ve been experiencing powerful insights about the future of transportation. Today I give you these insights as three predictions.

1. Streetcars redux

Two models

Waymo’s service can be thought of as one model of AV operation that I’ll call fleet service. Fleet service uses vehicles equipped with many sensors (especially LiDAR). They operate in geofenced zones measured with 3D maps that are meticulously recorded and updated regularly. The model is unspecific to the vehicle’s body type or mode of ridehailing: for example, Uber’s partnership with Volkswagen involves ID.buzz vans and could do “pooled” rides or shuttles. Nor is the model specific to Waymo. Baidu’s Apollo Go runs similarly.

Contrast fleet service with Tesla’s (proposed) universalist model, whereby vehicles equipped with only cameras can operate at level 5 autonomy without maps. The driving model is also trained using end-to-end learning although this is not as qualitatively important. The point is that the vehicles could be either for ridehailing or personal use, because the technology is inexpensive and works anywhere.

I’m not an expert on the tech, but I am skeptical of Tesla’s ambitions for a few reasons.

The experts I’ve talked to in academia and industry are skeptical.

When Tesla executives talk about foregoing LiDAR/maps, they seem more convincing about LiDAR’s drawbacks (expensive, or power inefficient, or ugly) than they do about camera-only working. It’s like hearing someone say we should drink seawater because freshwater is scarce.

The shamelessness of Musk’s bullshitting about Tesla speaks to carelessness about objective truth. The Cybercab will cost $30,000 in 2026, and in 2020 Teslas will earn owners up to $30,000 per year in passive income. At least change the number. FSD can’t read signs. Robot bartenders. Cybertruck falls apart. “Passive income.” Granted, people with skin in the game at major investment firms seem to buy it, so I could be missing something; but it all comes across as pitched to a guy who thinks that the mattress store is really going out of business. Were you stoked about Fyre 2? How do you react when a sign says World’s Best Cup of Coffee?

I guess we will see, but it is worthwhile to contemplate what the future will look like if fleet service remains the dominant model of autonomy.

Natural monopolies

Fleet service is a natural monopoly. In the first place, it involves high fixed costs and barriers to entry. Some of these are local: e.g., the maps, regulatory approval. Others are global: e.g., the trained models and experience gained from learning-by-doing.

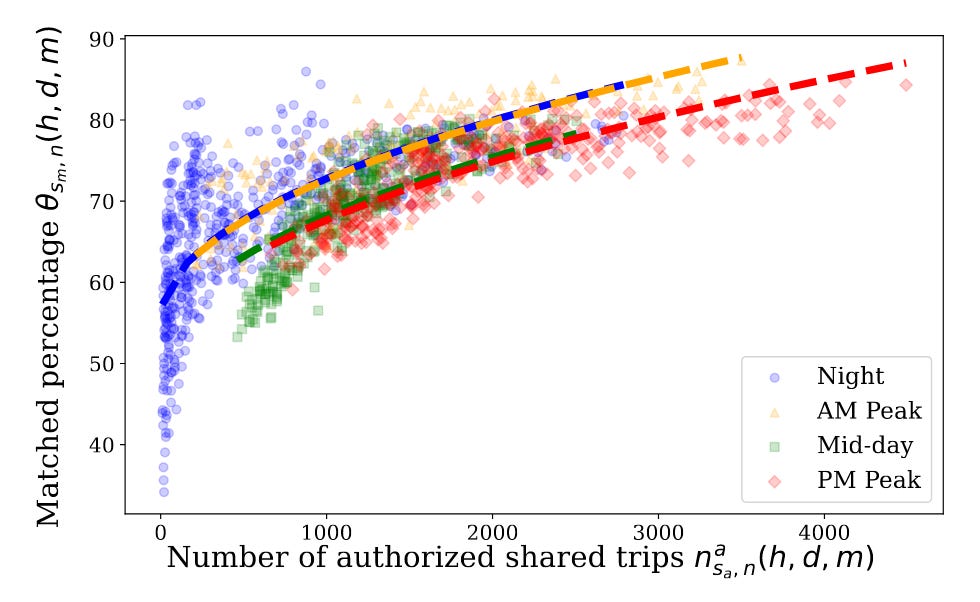

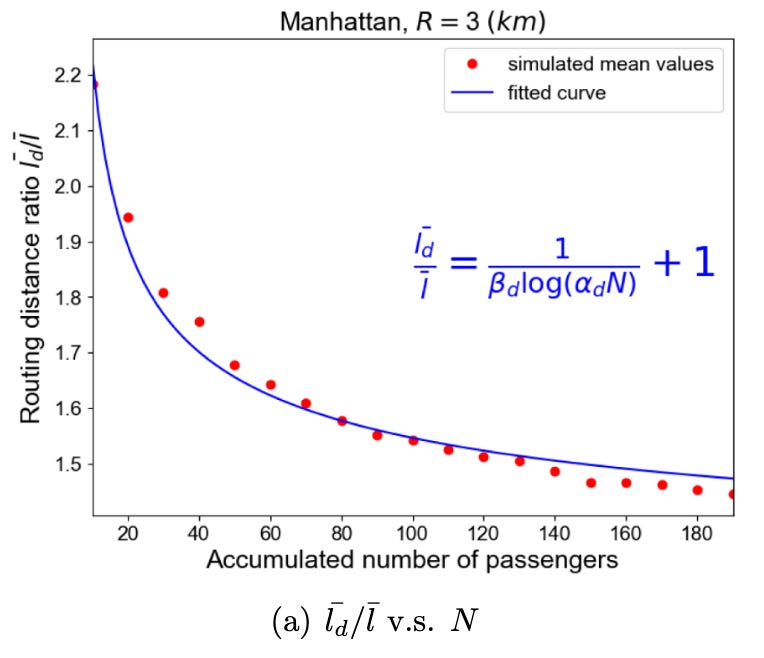

Ostensibly, with time, a frenzy of (over?)investment could erode the cost barriers. More fundamental are increasing returns in ridehailing per se. A TNC with many vehicles (autonomous or not) floating around will have lower wait times than a smaller one. Hence there are only two real TNCs in the US and one in most countries. For “shared” service (such as UberX Share, Uber Commute or ostensible shuttles), these returns increase even faster. A large incumbent can match trips more often and with shorter detours than an entrant with small uptake. See graphs below. Hence only Uber still offers shared ridehailing in the US, since Lyft and Via have exited.

The upshot is that, even if there are multiple firms in a country offering fleet service, just one firm will wind up dominant in each city. Similarly, after privatization in the 80s, British bus companies competed robustly for a time but then consolidated such that different cities and parts of cities (other than franchised London and now Manchester) are dominated by single firms. Thus, the future will recapitulate the era from about the 1870s (depending on the city) until about 1930. In this era, urban passenger transport was a utility provided by scale technologies such as elevated rail, cable cars, funiculars, aerial trams and (especially) electric streetcars. Check out this history of transit to learn more.

Two Americas

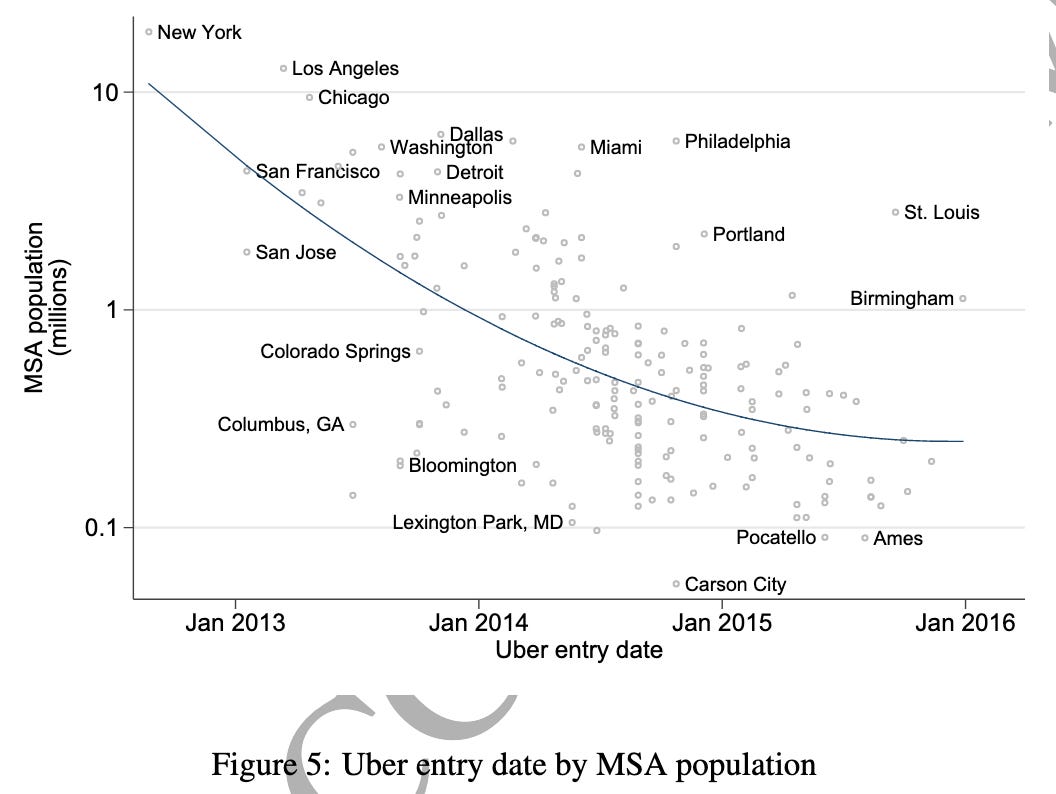

From 2013-2018, the TNCs expanded from major cities, to small cities and finally to many rural areas across the US. Look at this graph.

It may be natural to think that, after a time, you’ll be able to hail an AV taxi almost anywhere, too. But a sharp divide will persist between places with/without fleet service—just as there were places with/without streetcars.

One reason you can get an Uber in Walker County Alabama is Walker County is someone’s home. There are drivers living around there who will not move to Atlanta even if they can earn more. By contrast, an AV taxi has no attachments; its owner will move it where the money is. So expect a “law of one price” for the time of the AV taxi: AVs will earn (very roughly) the same rate of profit per hour anywhere that they operate regularly. Places with demand too low to yield this return at any price will not have service—just like places that are too small don’t get Costco. In turn, the cost of mapping elevates the floor of necessary demand.

The upshot is that, to an AV, a map of the US will look like a map of the Rus to a Viking: you’ll be able to move within and around areas around cities, and across the country on interstates that snake over the land like rivers. But the cities will have walls and you won’t be able to go far from the interstates in between them (e.g., Breezewood but no farther). The divide will beget tropes about the “two Americas.” Country musicians will never shut up about driving. President Vance will speak for the drivers whom global elites have left behind.

Politics

During the streetcar era, regulation, negotiations and corruption around their concessions and regulations played a major role in city politics. Similarly, populists will occasionally crusade for regulating fares or shorter wait times in some neighborhoods. But there are fewer “sunk costs” than for streetcar service, so in response to a too-unfavorable policy, a provider can temporarily move its vehicles elsewhere to punish a city. Minneapolis got a taste of this last year. Hence a Zohran Mamdani of 2035 may campaign for publicly-owned AV taxis—like how Chattanooga has municipal broadband.

An interesting political development will be the emergence of 3D mapping as new public good (or perhaps a club good). Some cities will pay for their city to be mapped and included in AV networks like they pay for roads now. Legislators from exurbs and small towns will fight for tax dollars to fund mapping like they fight for road and school money. There will be subsidies for operating costs to realize the “returns to scale” element: e.g., Waymo would be paid enough to break even in some marginal area—just as the governments subsidize rural intercity bus service and airports.

2. Fully automated luxury inter-Buc-ees coach service

Consider two news items:

Kea Wilson at Streetsblog asks: “Is the Intercity Bus About To Have Its Big Moment?” pointing to the latest Intercity Bus Review by Joseph Schweiterman and Zaria Bonds at the Chaddick Institute. Enterprising firms (many Texan) are offering a nicer experience in new places. For example, Gogo Charters in the midwest. Governments are launching new services like those in Colorado and Virginia.

Aurora started commercial autonomous truck service in Texas.

I predict these herald the era of Autonomous Coaches (AC) in about ten years. Ten theses on ACs:

ACs’ main advantage will come not from eliminating the driver’s wage (at least in the short run given how expensive autonomy is) but rather eliminating constraints inherent to humans. Drivers are subject to federal hour limits (here) and need breaks, and like any employee there is some challenge in hiring them for specific events or seasons in particular places. The AC routing/scheduling problem is less constrained. Consequently:

ACs will rarely be idle other than for maintenance, cleaning and fueling.

ACs will “deadhead” themselves to always be in the right place at the right time. After a shift ends in Charlotte at midnight, an AC could head to a depot in Greenville for cleaning and refueling, then to Atlanta to take a group of families home to Savannah from graduation at Georgia State.

Eliminating driver breaks and rotations will save passengers in-vehicle time. The longer the trip, the more time is saved. So there will be more demand for long, direct trips—especially overnight.

ACs will benefit from the existence of AV taxi/shuttle fleets within cities in two ways that have nothing in particular to do with the bus’ autonomy:

ACs will mainly drop off/pick up at travel plazas (like Buc-cees) outside downtown areas, while AV taxis or shuttles will carry passengers on the “first/last mile.” A route from Indianapolis to Milwaukee might stop at plazas on 294 as it passes Chicago. This division of (robot) labor will provide shorter door-to-door times and avoid the uncertainty, liability, curb space demand and compute involved in sending a hoss through a city proper. The highway between two cities is the overlapping part of all journeys, so that’s the part people will share. If an AC visits a small city or college campus without 3D maps and/or AV taxis, a remote operator might drive it to a pickup point.

AV taxis will raise the demand for intercity travel and permit ACs to compete with “driving yourself” between cities, since you won’t need a car at your destination.

#1 and #2a mean a given stock of ACs will serve a lot of route-miles. This mileage translates to some mix of more frequent departures, larger networks and more direct routes. The resulting convenience of a thick schedule will increase demand, making a larger fleet profitable, and so on in a positive feedback loop. #2b will complement this positive feedback.

Unlike AV taxis, ACs will not be electric unless and until there is some major advance in hydrogen fuel cells or solid state batteries, because they will be heavy and stay in motion as much as possible at interstate speeds. Still, ACs can be regulated to run “greener” than today’s diesel buses by using CNG or LNG.

ACs will typically have “hosts” who make manage luggage and boarding, make passengers feel safe, serve meals, make sure Wifi works and fix bathrooms, etc. I have ridden this sort of “executive service in Peru and Colombia: e.g., Peru’s Cruz del Sur. See also Texas’ Vonlane. Hosts undo some of the logistical advantages of eliminating drivers (since they need to go home), but they can work longer shifts at shorter intervals. Their wages will also be lower than a driver’s would be, since driving is a licensed profession and exhausting.

There will be major variation in AC size.

Some ACs will be absolute units like the Autotram Extra Grand or Neoplan Jumbocruiser. This space will go toward far-reclining seats, multiple bathrooms, lounges/work areas, maybe even small “cabins.” Large sizes will be practical, because (i) ACs will stay on the highway per #2a; and (ii) the risk of error and thus liability costs will be lower. Note it is not only ACs’ risk of error that will be lower, but also the risk of error from other vehicles on the highway such as increasingly-automated trucks.

Depending on how costs shake out, a journey in a small AC may cover its costs at a given fare with fewer paying passengers than one today. These will not have as many amenities, but they will run at high frequencies on short routes (e.g., Philadelphia to Newark). It’s possible they could operate without hosts using facial recognition cameras for security.

Service will be provided by national and super-regional carriers, rather than a mix of different firm sizes like intercity bus service today. The edge autonomy grants is staying in motion, which is more useful in a large network with many places to go. Large networks can also more easily circulate hosts and maintenance staff around depots and back home. But while certain providers will be somewhat dominant in certain regions, there isn’t as strong a tendency to natural monopoly for coach service as for AV taxis. I expect this market to be more competitive—more like air travel than like TNCs.

Geographically, the biggest beneficiaries of ACs will be cities too small to have major airports (especially college towns and state capitals) but large enough to merit visits from ACs. Life in such places will feel more convenient and connected to the rest of the country. It will be easier to draw workers to a corporate HQ like ADM in Decatur, IL or to a university like Penn State in State College, PA if they can ride in comfort to a major city whilst working.

ACs will reorganize air travel. There will be a first-round diversion of some passengers on middle-distance trips e.g., Birmingham to NOLA, St. Louis to Chicago, Atlanta to Jacksonville. Over such distances, while slower, ACs will be more comfortable and not involve TSA. In turn, these flights will be offered less often and become less convenient, diverting more trips, and so on. In the end, some small airports will cease mass passenger operations. Surviving airports will reallocate capacity toward long-distance flights and freight. The government will bail out some mid-size airports.

The proliferation of ACs will “shrink” Middle America and beget much more travel to/from places you wouldn’t think about. Millions of people in this country almost never go or even have gone anywhere because they can’t drive at all or very far. Some of this travel will be medical in nature: seeing the best specialist for your rare condition. But much of it will be tourism. Imagine your vision keeps you from driving far from Terre Haute, where you grew up. One day you and your best friend take a Lyft downtown, where a beautiful new bus whisks you away to a weekend in Louisville. The seat reclines but you just can’t sleep because it’s all too exciting and you have so many questions for the nice man in uniform who pours you a glass of wine. To readers of Critical Density, the bright lights of the River City might not sound overly memorable. But an authentic mint julep on an authentic steamboat, the Kentucky Derby Museum and a stay at the Hilton Garden Inn will amount the thrill of the century for someone whom the automobile age has otherwise left to rot in front of an iPad.

3. Central Business District Tolling Program

People keep asking me if CBDTP will survive, since I am the foremost authority on the history of downtown congestion pricing. Things look rocky: while my fellow Lewis J. L is defending the city, the imperial forces are determined to pillage.

My prediction is that Manhattanite Barron Trump will soon launch and win a dark horse candidacy for Gotham’s mayorship. With guidance from his formidable mother and one-time rival Eric Adams, the colossus will shield New York from his father’s meddling (including on CBDTP) whilst coming of age and coping with the pressures of college life.

If this prediction fails I will write a YA novel about it called Big Apple, Big Mayor. To appeal to the youth, in the novel Eric Adams will turn out to be a Twilight-style vampire. This will explain:

his wardrobe,

inconsistent reports of what he eats,

endless nightlife at “age 64,”

why he transits through Istanbul—he died in the fall of Constantinople and needs earth from there on a regular basis. The “corruption” was actually blackmail by Erdoğan, who discovered Adams’ secret and is himself an ancient vampire. Trump dropped the charges due to Barron’s intervention.

These are my predictions. Maybe they strike you as “out there.” But if you recall my earlier posts, I predicted congestion pricing. I predicted it would be a big success. And people smiled, George Stephanopoulos laughed, you remember. He thought it was very cute, and very funny. Other people smiled. But some people, the smart people or the people that know me, didn't laugh at all.

If the bus is autonomous, who will we thank when we get off? That is my main concern.

Did not expect to see a Jasper Mall mention in this newsletter! Hope you say my name in the credits. 😉